When discussing what is needed to solve climate change, there is a knee-jerk response: renewable energy. As a result, forecasts showing renewables poised to surpass coal as the largest source of electricity by 2025 are assumed to be a positive and progressive development. And from a purely carbon calculus, this often is the case. But, because renewables — solar and wind energy in particular — are encased in a kind of impenetrable progressive halo, few actually examine the political economic forces shaping the industry.

Amid this collective myopia, we have not noticed that an economy powered by renewable energy does not guarantee a fairer or more equal society, or one that favours workers over the interests of capital. When you take a look at the dynamics of existing renewable energy production (particularly in the United States) you find that it intensifies and exacerbates all the worst aspects of our highly unequal neoliberal political economy.

To understand these dynamics, we need to look to the Seventies and the rise of neoliberalism. During this crisis decade, power and influence was shifted toward capital and an associated free market ideology. Though often portrayed as anti-government, neoliberals in fact promoted quite an active state, creating the institutional conditions for markets, the extension of private power, and above all the insulation of states from democratic control. One of their greatest influences, Friedrich Hayek, had argued against “central planning” in favour of a different kind of system: “Competition…means decentralised planning by many separate persons.” The expanded Keynesian redistributive state was their prime target, but this critique extended to all kinds of large-scale bureaucratic institutions: unions, universities, and even massive monopolistic corporations of the time, such as General Motors or IBM.

In other words, neoliberals set their sights on the very institutions at the heart of the post-war boom. Their vision of a new competitive market order aimed to demolish these large, rigid institutions in favour of smaller, more flexible production guided by a decentralised price mechanism. It was an ideology that seized the electricity sector at precisely this historical moment. For most of the 20th century, electricity had been provisioned by massive investor-owned and vertically integrated utilities — each given a “natural monopoly” service territory where they controlled the entire grid. State-run public commissions oversaw these utilities to ensure consumer prices and investor returns alike were “fair and reasonable”. Because electricity is in fact a complex infrastructure where supply and demand must always remain in balance to preserve grid stability, utilities centrally planned the grid by necessity.

In the context of the Seventies energy crisis, electric utilities epitomised the kind of inflexible and corrupt institutions targeted for demolition. And, interestingly, an associated environmentalist ideology conformed to this neoliberal critique of “big” and “centralised” utilities. Most prominently, Amory Lovins proposed a “soft energy path” based on small-scale and decentralised energy production and efficiency. Although Lovins promoted any kind of decentralised energy production — including many small-scale forms of coal generation — soon it became clear that renewable energy production from solar panels and wind turbines were the most attractive to environmentalists.

Advocates imagined a shift to renewable energy aligned with a “small is beautiful” approach, scattered about pastoral rural landscapes, and inspiring ideas of local or community ownership. Against a complex and centrally-planned system, “grassroots” local communities aspired to get off the grid entirely. In short, if most of the 20th century was about large-scale social integration of complex industrial societies, the neoliberal turn represents an anti-social reaction against society itself. For parts of the Right, there was “no such thing” as society, only individuals. But the environmental Left made a comparable turn: large-scale complex industrial society was rejected in favour of a small-scale communitarian localism. In this framework, “communities” could opt out of society and usher in democratic control over energy, food, and life. As the icon of the German Green Party Rudolf Bahro said in the Eighties, “we must build up areas liberated from the industrial system…a new social formation and a new civilisation”.

It should be no surprise that Lovins’s soft energy path ideas gained the ear of proto-neoliberal and deregulator-in-chief, President Jimmy Carter, who invited him to the White House in October 1977. Carter personified this new decentralised energy ideology, wearing cardigan sweaters in his prime time addresses and decorating the White House with solar panels. But while environmentalists often lament the path not taken with Carter’s conservationist ethic, his approach to the energy crisis (among other things) was a political disaster. Ronald Reagan crushed Carter by nine points in 1980 and Carter only carried six out of 50 states. For a country that had just endured a cost-of-living inflationary crisis of its own, Reagan’s message of “Make America Great Again” and solving the energy crisis through increased production resonated much more strongly than Carter’s moralism and calls for sacrifice.

But what is crucial is how this vision of a decentralised renewable-powered utopia actually accompanied a broader project of electricity deregulation started under Carter himself. About a year after meeting with Lovins, Carter signed the Public Utility Regulatory Policies of Act of 1978. Deregulation eventually opened up the field of electricity generation to competition against utilities. The process was slow but by the Nineties it unleashed a totally new frontier of investment in electricity production for capitalists untethered from the utility system: so called “independent power producers” or “merchant generators”. The main beneficiaries of this process were smaller-scale natural gas producers, but it also included a new class of capitalists building renewable energy projects such as solar or wind farms. These producers need not care about the grid as a shared social system, and can focus instead exclusively on their private profits and efforts to outcompete other sellers in wholesale electricity markets.

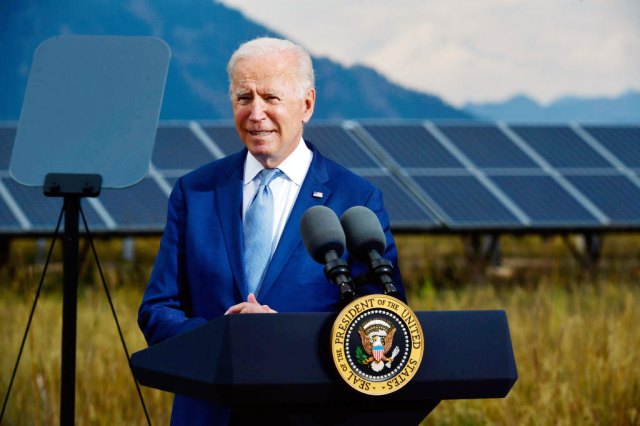

Profit could also come from the state itself. As research by Sarah Knuth shows, by the Obama years, renewable energy capitalists were showered with lucrative tax credits to incentivise production. The credits allow renewable energy developers to partner with an exclusive class of “tax equity investors”: a special kind of wealthy person whose “tax burden” is so high they use renewable projects to shelter their wealth from public coffers. These tax equity investors represent some of the most powerful and wealthy actors imaginable, such as Goldman Sachs and Bank of America. Warren Buffett — whose company Berkshire-Hathaway is one of the biggest investors in renewables — famously said, “We get a tax credit if we build a lot of wind farms. That’s the only reason to build them.” Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act is simply a continuation of this policy of attempting to achieve climate goals through the tax code (albeit with a “direct pay” provision that will allow some public power entities to take advantage).

This shift away from utilities and toward decentralised merchant generation explicitly undermined the labour unions who had built up their power under the older, established utility system. As James Harrison, the director of renewable energy for the Utility Workers Union of America, told the New York Times, “The clean tech industry is incredibly anti-union… It’s a lot of transient work, work that is marginal, precarious and very difficult to be able to organize.” It was, therefore, no surprise that labour unions were on the frontlines fighting deregulation from the beginning in the Nineties. It is much easier to organise workers in centralised power plants than scattered solar and wind farms whose, after all, only provide temporary construction jobs.

Once these installations are built, the jobs disappear and the only plausible economic benefits besides rents flowing to private landowners are marginal increases in local tax revenues. Not only are renewable energy jobs temporary, they are also often simply bad jobs. Labour journalist Lauren Kaori Gurley’s profile of the solar industry has revealed dystopian labour conditions: temp agencies send subcontracted workers from site to site, separated from their family for weeks, and exposed to occupational hazards such as extreme heat, alligators, and snakes.

Neoliberal electricity restructuring is benefiting Wall Street above all, as well as Big Tech, who see it as a more efficient means to partner with renewable generators and claim green credentials for operations powered by “100% renewable energy” (these accounting fictions are provided by tradeable Renewable Energy Certificates while firms still rely on the fossil- and nuclear-powered grid for their actual electricity). Google has emerged as a fierce proponent of deregulation in the American South fundamentally so it can avoid utilities and partner with more scattered renewable capitalists. Naive environmentalists (who propose an extremely difficult vision of a grid powered by 100% renewable energy) have become unwitting allies of the Googles and Berkshire Hathaways of the world — and fail to recognise their renewable advocacy often enables the further neoliberalisation of electricity.

Seduced by climate rhetoric, the Left has become the unwitting ally of this programme. But the electricity grid is a shared social infrastructure that should be managed by a single entity. In other words, while private investor-owned utilities are often corrupt and negligent, the Left needs to defend and reclaim the general idea of electricity as a utility, or an essential service critical to the public good. A revived electric public utility system could indeed integrate some renewables in sunny and windy regions (on land and offshore), but grid planners will acknowledge some level of “firm” low carbon generation like hydroelectric and nuclear power will be required. But this vision of public energy development won’t come about unless we confront the power of renewable capital, their Wall Street backers and the general neoliberal political economic model that underpins the industry today. Sloganeering around renewable energy as if it’s a good in-and-of-itself may have drawn attention to the climate crisis — but it is no good at creating the politics we need to solve it.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe