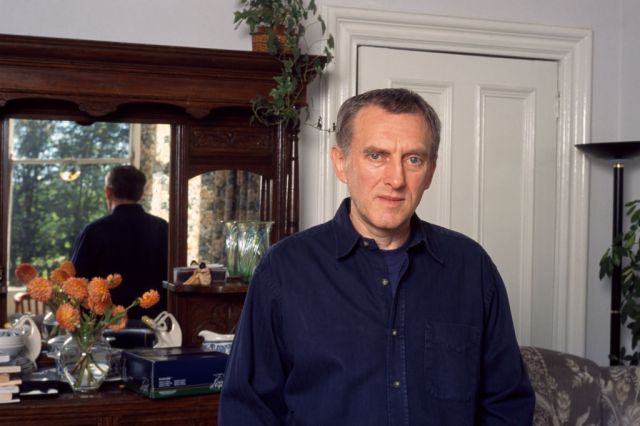

James Kelman. (Louis MONIER/Gamma-Rapho via Getty)

Modern politics is a business that obliterates the self. It turns its winning practitioners into one-dimensional media-facing personalities schooled for the soundbite and the photo-op. Yet plenty of voters, and news outlets with gnat-sized attention spans, still hanker for glimpses of a private hinterland of tastes, preferences, even passions. The spin machine duly delivers this as a Potemkin Village of confected enthusiasm for beloved sports teams, pop stars, Hollywood movies and the like. David Cameron, for instance, was supposed to be an Aston Villa fan until, one day, he forgot the agreed script and disclosed a hitherto unsuspected devotion to West Ham United. He blamed “brain fade”.

Now take our new Prime Minister. Does he have a favourite book? Pre-election profiles suggested, unexpectedly, that he carried a flame for James Kelman’s 1989 novel A Disaffection: the Glaswegian writer’s virtuoso monologue, which voices a young teacher’s dark night of the soul. Legal colleagues have reported that the former DPP admired and absorbed Franz Kafka’s The Trial (not such a surprise). Then a cagey interview in The Guardian portrayed an opaque figure with no particular novel or poem to champion.

The Kelman salute allegedly came from Starmer’s 2020 appearance on Desert Island Discs. Listen to the episode in question, however, and you find that, in addition to his “luxury” (a football), the future PM actually picked as his reading-matter not existentialist fiction from Scotland but “a detailed atlas, hopefully with shipping lanes in it” — so that he could plan an escape. His affection for A Disaffection seems to derive from a Labour Party fundraiser in Camden in 2019, which featured a Desert Island Discs-style event.

The two lists — one for his local party comrades, the other for Radio 4 listeners — reveal other notable discrepancies. Among his musical picks, Beethoven’s Emperor concerto and Jim Reeves (a favourite of his mother’s) survive. But Starmer’s NW1-based love for Desmond Dekker’s ska classic “The Israelites” and Shostakovich’s second piano concerto — genuinely interesting choices — gave way in the BBC studio to a dismally predictable nod for the Lightning Seeds’ “Three Lions”.

So the verdict on James Kelman from 10 Downing Street remains — as with much about its new incumbent — a matter of speculation. But if Starmer does understand and appreciate the 78-year-old novelist, short-story writer and social activist, so much the better for him. An easy “gotcha” trap looms here that it would be wise to avoid. Famously, Kelman is a radical socialist and internationalist, albeit with a fiercely anti-state, even anarchistic, streak. In works such as the Booker-winning How Late It Was, How Late, he deploys the abrasive and profane vernacular of the West of Scotland to express the pain and rage of poor people crushed by overweening power. And Starmer is — well, we know what, in political if not personal terms. Kelman, whose protagonist in his latest novel inveighs against “elitist fuckers, racists, monarchists, imperialist bastards”, has over the five decades of his published work exhibited sub-zero respect for London lawyers, Labour politicians or senior UK state officials. Starmer neatly ticks each box.

So: bland centrist apparatchik loves potty-mouthed hard-Left diehard who would happily string him up with his own red tape? Let’s hold back on the sarcastic sneers for a moment. What matters is not Starmer and Kelman’s notional positions on the light-pink to deep-red spectrum, but the novelist’s rare ability to endow the inner lives of people “left behind” by money, status and power with grace, depth, even grandeur. All politicians should take heed of such a gift. Kelman is not just a polemicist and campaigner — courageous and stubborn, for instance, in his support for victims of workplace asbestosis poisoning — but a deeply serious literary artist. A disciple of modern literature’s giants of innovation in language and vision (Samuel Beckett, Franz Kafka, Albert Camus, Knut Hamsun), he invests the working-class life, thought and speech of post-industrial Scotland with all the nuance, scope and subtlety that Marcel Proust attributed to Parisian aristocrats or Virginia Woolf to the denizens of upper-bourgeois Bloomsbury.

Always a voracious reader, Kelman laboured on building sites and in factories (one, in Manchester, exposed him to asbestos) before, in the early Seventies, he joined open creative-writing classes in Glasgow run by Philip Hobsbaum. This poet-academic had a quite extraordinary record as a literary mentor. In Belfast, his apprentices had included a young teacher named Seamus Heaney. In Glasgow, Kelman’s classmates would constitute a galaxy of future Scottish stars, from the poet Tom Leonard to the artist-novelist Alasdair Gray. So Hobsbaum’s writing students have won the Nobel (Heaney), the Booker (Kelman) and now, via the film adaptation of Gray’s Poor Things, four Oscars. By 1973, Kelman had published a volume of stories while still working as a bus driver. He got no advance, but his 200 author’s copies arrived just as he set out for a winter dawn shift.

In the Eighties, sporadic critical acclaim did nothing to blunt his cutting edge. When How Late It Was, How Late took the Booker, to the outraged howls of various critics and even a couple of judges, journalists gleefully totted up its 4,000-odd “fucks”. “My culture and my language have the right to exist, and no one has the authority to dismiss that,” Kelman retorted. But the novelist — raised in Govan and Drumchapel, his father a skilled picture-framer and his mother a late-qualifying teacher — has never transcribed street talk into agitprop fables. On the contrary: his finely-wrought streams of consciousness and deadpan comic dialogue make uncompromising art from suffering and victimhood.

Sammy Samuels, the blinded hero of How Late… dragged through a torturous “daymare” of arrest and imprisonment, descends not just from Kafka’s Gregor Samsa (in The Metamorphosis) but Milton’s Samson Agonistes. Kelman’s short stories — with collections such as Greyhound for Breakfast (1987) among the strongest of all his works — bring the sensibility of Beckett and Chekhov to the boredom, panic and fitful joy of joblessness or drudgery around the Clyde. A Disaffection met a warmer reception from what he would call “establishment” critics than his fiction often does; according to the author, because its glumly erudite protagonist, although of working-class origins, shared their frames of cultural reference. Still, its torrential soliloquy of thwarted love and hope hits hard.

Praise Kelman and you laud not some facile cheerleader for the traditional proletariat in eclipse but a refined artist who shows that the blows struck by economic, and political, injustice drive people into tragi-comic states of soul. That plight stretches the limits of literary language and fictional form. “The stronger artists always make a challenge,” said Kelman recently: “not only do they write of people from… the lower areas of society, they work within the languages of these same communities. They do not assimilate.” Don’t look to Kelman for feelgood fightbacks against rustbelt adversity, Full Monty-style — although Alan Bleasdale’s Boys from the Blackstuff edges closer to his territory.

If Starmer does back Kelman, he votes not for condescending fairy-tales of pluckily-borne deprivation but tough, ambitious, experimental literature. The writer has spoken of his debt to “two literary traditions, the European Existential and the American Realist, allied to British rock music” — itself, Kelman notes, the offspring of Blues and Country-and-Western. From a British politician, a homage to any creative figure with such a complex pedigree would make a change. Besides, Kelman needs, and merits, the endorsement.

Even after the triumph of Kieron Smith, Boy — a searingly tender portrait of Glasgow childhood that, among other things, enabled Douglas Stuart’s Booker winner Shuggie Bain — his star faded and his income fell. His fancy publishers departed. Although one of his funniest, most approachable works, Kelman’s 2022 novel God’s Teeth and Other Phenomena appeared not from some grand imprint but a small California-based indie, PM Press. Piling insult on injury, it garnered hardly any reviews in UK media until this glaring neglect itself became a story, and prompted some catch-up coverage.

“Surviving is fucking hard,” muses Jack Proctor, the rebellious curmudgeon becalmed on a North American campus who narrates God’s Teeth… For Kelman, it has been, although his humour, outrage and resilience persist. Not quite a self-portrait, Proctor nonetheless sports several Kelmanesque traits, such as exasperation with his rep as “the chap who writes the swearie words” and a history of winning a posh accolade known as “the Banker Prize”. For Jack’s creator, some conspicuous applause — even from a metropolitan KC who heads what he would deem a sell-out party — might not come amiss.

In any case, Kelman’s work and stance may have something to teach the PM beyond the eternal sniping that Labour leaders expect from the Left. Notice that tribute to “Country-and-Western” in Kelman’s roll-call of the art he loves. In a talk to Texas schoolkids (given while he lived and taught in Austin), he numbered among his earliest inspirations Connie Francis, Buddy Holly, Sam Cooke and Fats Domino. Such musicians “sang in their own voice and for their own people”, motivated by “self-respect” and respect for their own culture. Scrupulously, Kelman refuses to draw any ethnic dividing-lines.

His sympathy with the downtrodden in a landscape of exploitation has always been utterly ecumenical. When he was 15, his family briefly emigrated to America. The teenage Kelman roamed hardscrabble California on formative journeys of discovery. Hillary Clinton’s “deplorables” became his kind of folk as much as Clydeside ex-shipbuilders or, later, the Nigerian peasant farmers and village story-tellers celebrated by one of his own favourite authors, Amos Tutuola. Perhaps this ideal of underclass solidarity is a sentimental myth: Dirt Road, the picaresque 2016 novel that captures his musical passions, culminates in a festival that miraculously blends the sounds of black, white and Hispanic America into a redemptive harmony. If so, it now feels like a myth that heals.

Read Kelman, as we should assume Starmer has, and you will learn the many meanings of disaffection: not just estrangement from a system that rejects its economic outcasts and cultural backsliders but from others and, eventually, from oneself. Social crisis becomes spiritual crisis. Where dominant institutions and — crucially — the language they wield inflict a widespread sense of worthlessness and failure, a new job or a new house alone may not staunch the inner wound. Kelman speaks from the unyielding Left but his diagnosis may help explain the West’s revolt on the Right.

His writing channels the lacerating emotions of humiliation and disempowerment that go with membership of despised, or sidelined, classes and communities. An essay on the apartheid-era South African writer Alex La Guma reminds us that “Nothing is more crucial nor as potentially subversive than a genuine appreciation of how the lives of ordinary people are lived from moment to moment”. The prime minister of a country in which 40% of citizens declined to vote at all needs to know that. Political disaffection will haunt the Starmer years. He should seek a “detailed atlas” of disgruntled souls. Kelman might help him draw some accurate maps.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe